Okavango Delta – Northwestern Botswana, Africa

October 18, 2007

We’ve all heard the saying. “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.”

While that may be the case in many places on earth, in the cruel deserts of Africa, that rule goes right out the window. Firstly, you don’t need to lead animals in Africa to water. They will go there themselves, often at considerable physical expense. Secondly, they will drink (while watching their backs), and they will stay as long as that water remains.

Each year during the rainy season in the dense highlands of Angola, accumulating waters flow down into the forest valleys and replenish the Okavango River. As the river emerges into northern Botswana and reaches the flat northeastern regions of the expansive Kalahari Desert, the river fans out like a vast tree-root system and forms a huge delta.

This great wetlands is created because a barrier fault line at its southern edge halts any further advancement of the river. Aerial and satellite images illustrate this remarkable aquatic footprint in Botswana.

The renowned Okavango is a rich ecosystem that becomes a mecca for countless animals during the dry season as they escape the heat and parched landscapes of the Kalahari. The lure of this moist refuge creates the largest annual movement of animals on the planet! And in October 2007, we were lucky enough to be part of their welcoming party.

Because the rainy season waters take so long to flow the 315-mile distance from Angola, they arrive in the Okavango during the early months of its dry season (May to July), creating a delayed blossoming of moisture in an area that dries up months earlier.

At its largest, the Okavango’s flood area swells to over 9,300 square miles (the size of New Hampshire.)

At its largest, the Okavango’s flood area swells to over 9,300 square miles (the size of New Hampshire.)

The Okavango is an oasis for trees, plants, fish, reptiles, birds, amphibians, mammals and the lucky few designated human visitors who can access it on reserved safaris. And the only real way to access it is via small aircraft.

Getting there by plane is half the fun. We were transported there by two rather young, fun-spirited pilots on a six-seat Cessna 206 (called “the Workhorse of the Okavango” for its non-stop ferrying of visitors in and out of the region).

They sure knew how to adeptly float the rising thermals of the African bush. At a comfortable and scenic flying altitude of just 4,000 feet, you can see hippos and elephants below as they migrate to water sources along hippo channels and trails.

Once you get to the Okavango, be ready for the experience of a lifetime, one that few will ever experience. This area is pristine, isolated, and unmatched anywhere on the Dark Continent. There are only a few remaining unaltered wilderness areas in Africa. This is one of the best. Safaris don’t get any better than this. No wonder Okavango visitors rarely offer a bad review of any visit. They get what they pay for, which is a good thing, for the price is not cheap.

Guests at the various camps are strictly limited in number by government regulations. This not only keeps the vast safari concessions areas from being overrun by crowds and vehicles, it guarantees guests an exclusive, incomparable wildlife experience.

The average guest density in the Okavango Delta is just one person per 26 square miles. Some of the very popular safari locations in other areas of Africa, particularly Kenya, can average 40-50 guests in the same size area.

Pom Pom Camp, our destination, is set in a beautiful location on a peninsula overlooking a year-round lagoon in the Nxabega Concession, on the western side of the Moremi Game Reserve.

After touching down on a dry, rudimentary landing strip in the middle of a wet, remote nowhere, my wife Ana and I immediately bathed in the mystique and delight of this location. It was so obvious we were deep inside Africa, and nobody was going to hear from us for several days.

This camp offers an excellent mixed safari experience, where visitors get up-close and personal with game via mokoros (wooden canoes), land vehicles, and motorboats when waters are high. Some limited-range walking safaris are possible, with ample gun support, of course. Night safaris are an added treat, and bring guests into the mysterious world of nocturnal wildlife.

Keeping with the government’s intent to limit visitors, Pom Pom Camp offered just

ten tents, an open-air thatched-roof main lodge, and a few support buildings. We were thrilled to learn on our first two days that just two other guests, sisters from Australia, were at the camp. Things got a bit busier when the “throng” arrived the next day — another dozen guests. There were more staff than guests, so every need was met in assuring a splendid visit.

With gasoline-powered generators serving as the only power source, and Cessna supply drops as the only way to stock it, Pom Pom Camp was nevertheless quite luxurious. Many of the male staff carried pistols, and powerful rifles during safari rides, for obvious reasons. Keeping guests alive and safe from predators was their first and foremost concern. Exquisite food and drinks came second. Should these guys fail in their primary mission, the food and drinks would just go to waste.

It wouldn’t be long before we understood exactly why senior camp attendant Seretse would tightly zip our tent flap at night and remind us that “under no circumstances shall you leave the safety of the tent and venture off in the dark. Should you forget this warning, it might be the last time we see you.”

We found this rule to have profound value, and willingly obliged. So Seretse found us safe, secure and well-rested in our tent each morning when he woke us at 6:30. “Knock-knock,” was his gentle introductory peep. If we were hesitant to stir, he’d repeat, a bit louder. “Uh-hmm. Knock, knock.” This struck us as extremely funny, as there was no wooden door on our tent (obviously), so he found it effective to just speak out the sound.

“Knock, knock. Good morning. Rise and shine. Your coffee is waiting ….. and so are the animals.” We’d poke our heads out from our comfy pillows, and see Seretse’s brilliant grin through the mesh. It was one of the many bright smiles we would see at the camp, and at other stops in Botswana and South Africa. The people appeared full of joy wherever we went.

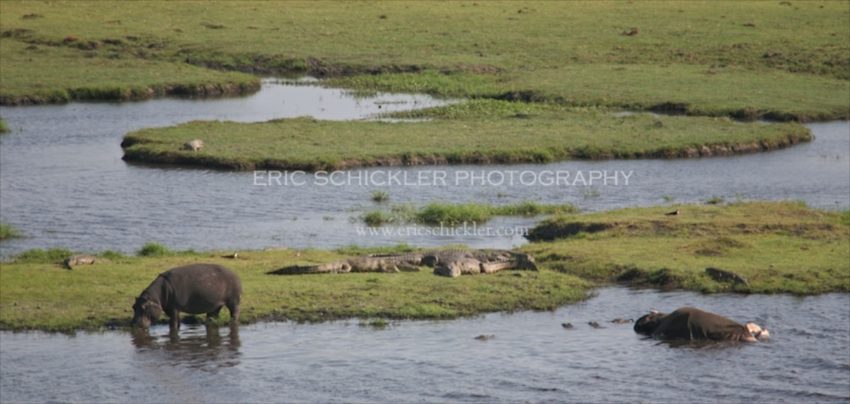

The juxtaposition of wilderness, wild predators and cushy accommodations was almost humorous. There was a hippo grunting in the muddy water just 20 yards from our tent, and leaving his messy droppings even closer when he roamed around the tent at night.

But inside our tent we enjoyed flip-on lights, high thread-count bed sheets, a cherry-wood bureau, a full bathroom and private open-air shower. The fresh-cut, fragrant flowers were a well-intended nice touch, but let’s just say the hippo droppings won out in the olfactory competition.

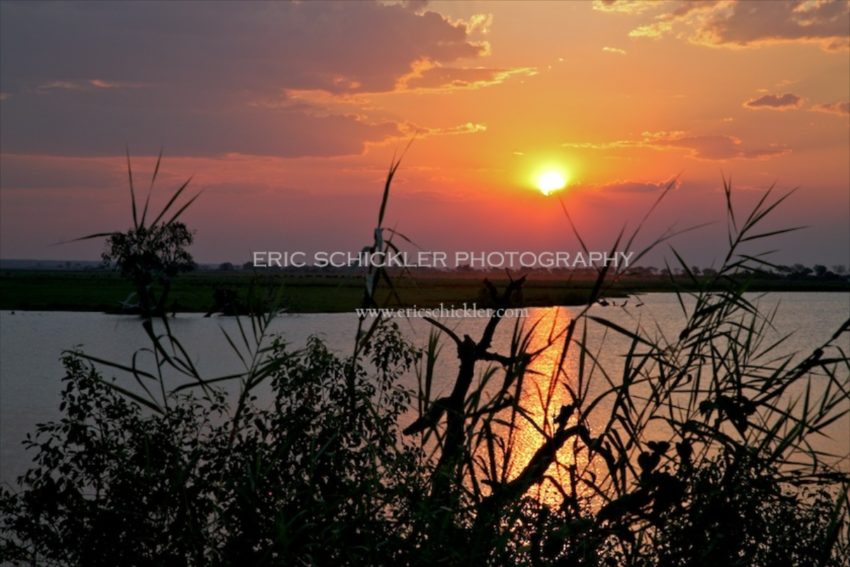

The daily pace and environment was generally slow, quiet and relaxed around camp. The excitement happened during our twice-a-day game drives. Cocktail happy hours were very popular with guests, at the quaint camp bar in the afternoon and late evening, around the dipping pool during the mid-day heat, and also out in the bush while stalking game just before sunset.

Our guides, Seretse, Ben, Vasco or Peter, would stop the vehicle and pull out the happy hour supplies: a small table, a festive African tablecloth, snacks, spirits, wine, beer, even ice cubes. When all was set up, and a scan of the area for predators was done, our guides would flash their big bright smiles and announce: “Time for a “sundowner.” Fortunately this relaxing social event was never upended by an unexpected raging animal.

The episode that follows starts out as a storybook African vacation experience, the setting painted through this introduction. But the story quickly turns into the startling reality of being face-to-face with one of Africa’s fabled Big Five predators, with practically nowhere to hide.

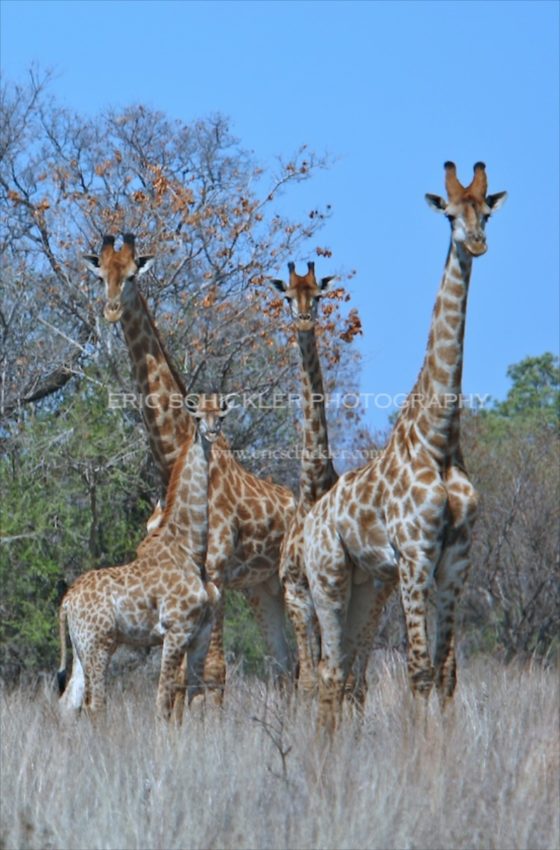

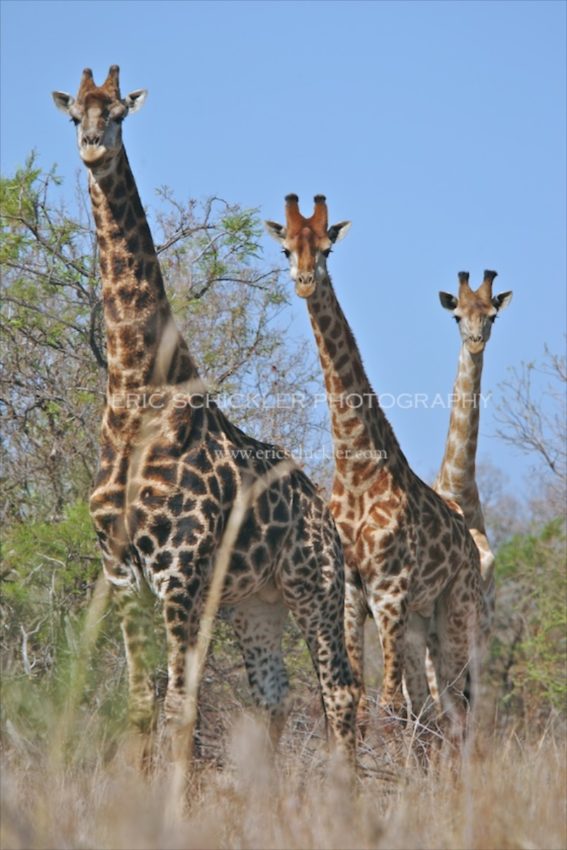

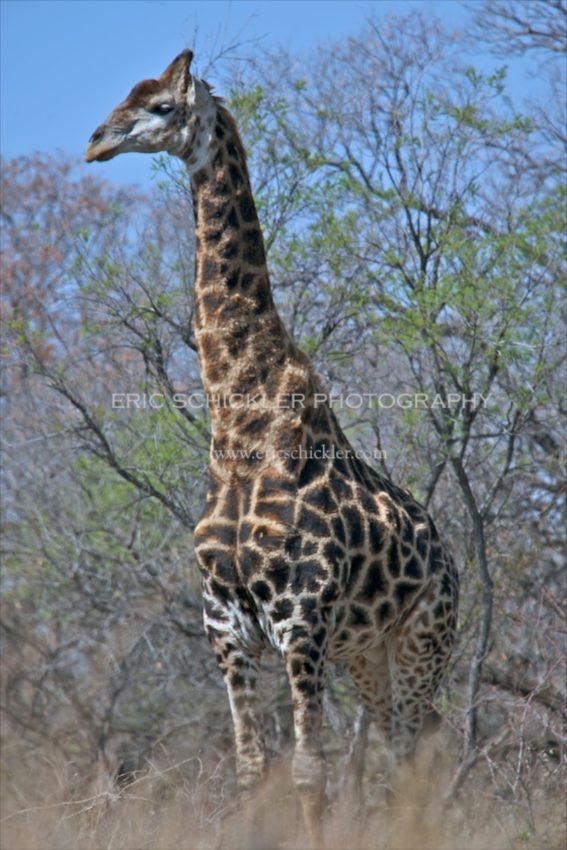

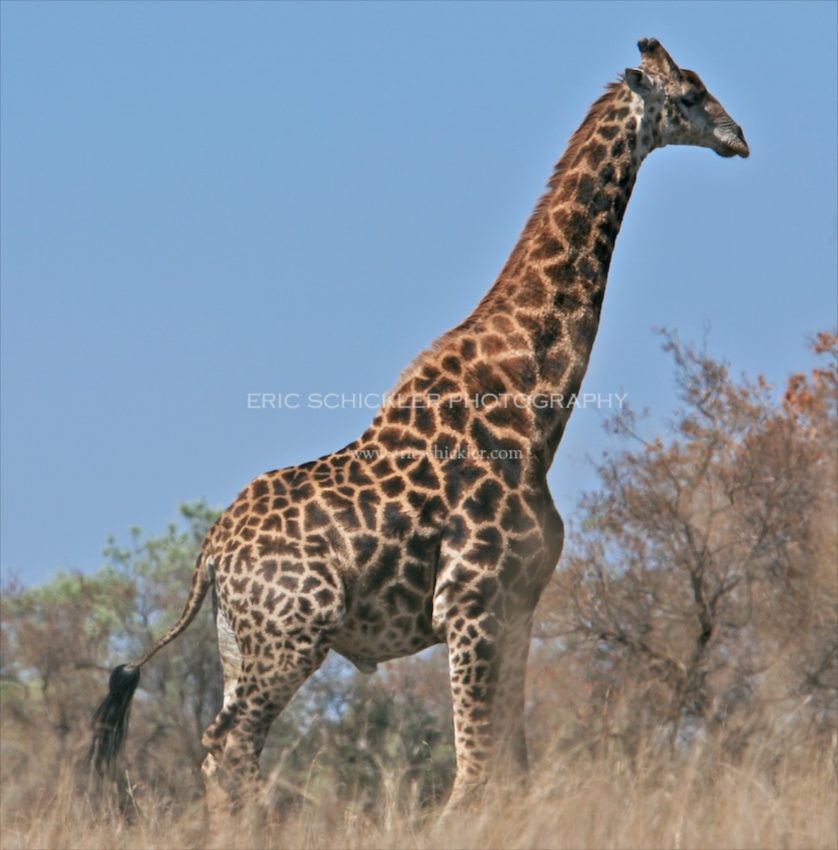

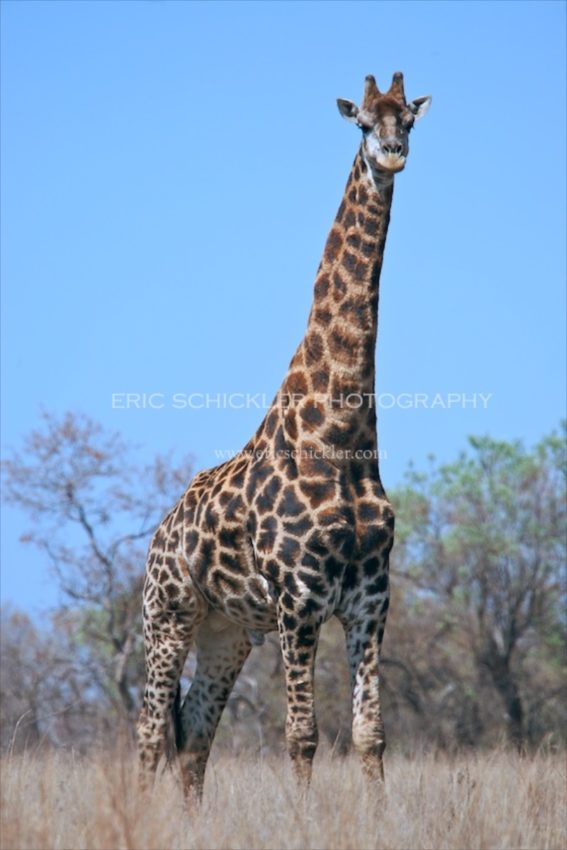

We had returned to our fortified tent to relax after a busy morning of game rides out in the African countryside. We got our money’s worth on the very first tour: spotting fish eagles, king fishers, birds of all kinds, exotic frogs. We saw ridiculous numbers of wildebeest, giraffe, baboon, zebra, hippo, warthogs, crocodile, waterbuck, kudu, warthog, impala, and a variety of antelope (including roan, sable and sitatunga).

Then there were the animals you didn’t want to meet up close: predators like lions, cheetahs, leopards, hyenas, cape buffaloes and wild dogs.

Ah yes, and one more. I almost forgot. (No I didn’t.)

I will never forget that other dangerous species, which commands the greatest attention because, well, they are rather hard to not notice. And because one of their bodacious centurions left a big impression on me and all the others at Pom Pom Camp.

We were off the safari truck and relaxing back at camp, but the animal interaction was far from over. It was all around us at the camp. Hence the necessity for gun-toting escorts to and from our tent and the main lodge each evening.

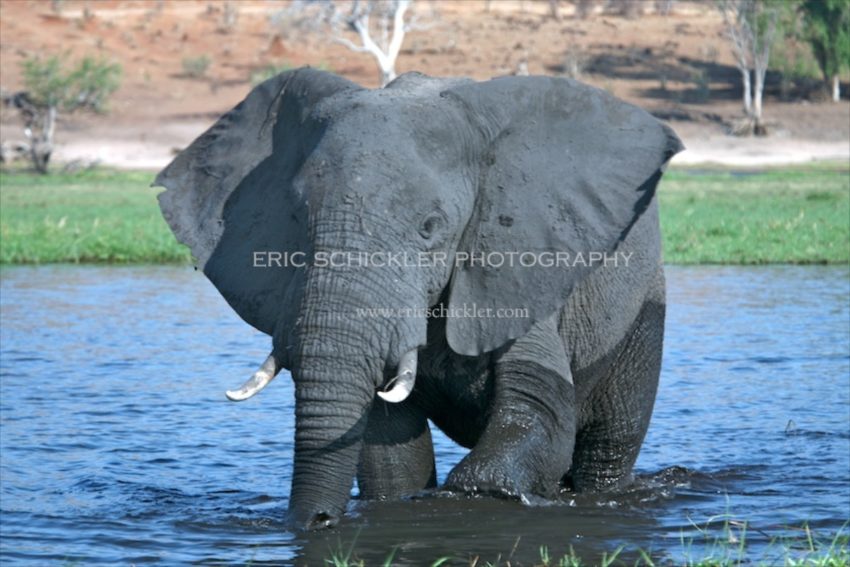

As we lounged in and around our tent on that warm lazy afternoon, off in the distance in the delta waters, right there in our own slice of solitude, emerged a very large bull elephant. He was rummaging through the delta, slowly making his way toward us as I watched, amazed. He was doing what male elephants routinely do in Africa: soak themselves in the water and the mud, show off and generally express their macho dominance and authority to the hapless camp guests. It was his opinion, and a correct one, that we were new to the camp and needed to learn whose playground we were in.

As a photographer, this was the most wonderful scenario I could imagine. We spent four hours on our morning ride, several miles from camp. We saw plenty of wildlife, but it required plenty of driving around looking for those animals, and me training my long camera lens in the distance for the photos.

But now here we were, just hanging out at our own little tent-side oasis, enjoying cold drinks after taking cool showers. I was still clad in a towel on our deck, facing the delta, not too concerned about the dress code here deep in the African bush, when I spied him off in the distance.

Running for my camera gear, I nearly lost the towel twice. Fortunately, my wife, our local hippo and this beast were the only living creatures with a view. Needless to say, modesty was not an issue at this point.

The stare-down from a distance.

After bathing and spraying himself in mud and generally showing us that this was his own private muddy bathtub, the elephant resolutely decided bath and shower time were over, then matter-of-factly turned on a dime, looked directly at me–the tourist photographer–and rambled my way. Rather resolutely. Rather directly. Even from this distance–some 250 yards–I could see he was staring me down.

Ana was in the tent doing something, perhaps writing some postcards. I set the camera down on the table, and issued my first “Elephant Approaching!” warning of my life.

We retreated quickly to the tent, hoping what camp manager Niles said was true, that the elephants won’t attack you in a fortified tent.

We found the exact epicenter of our shelter, believe you me. And we stood there, kind of holding each other, hearts pounding, adrenaline pumping, and beads of sweat emerging on our foreheads. We waited to see if that monster was going to crush our meager dwelling, and us with it. Please, no. We just got here. The postcards aren’t even written!

Then he moved insanely close to the tent–just ten feet–and walked slowly alongside it. With our breathing in suspension, our eyes followed four tree-trunk legs as they lumbered past the windows of the tent. All we saw were knee caps and calves, as we stood motionless with our hands over our mouths.

Fortunately he was more interested in munching on the tree branches next to our tent than on us. We scrambled to the back of the tent to the open-air shower, and from there saw the top of the beast. We felt great relief as he ambled away from our tent and down the camp trail.

We dodged a very big four-legged, one-trunk, two-tusked bullet, and congratulated each each other on the fine African adventure we had just survived. Then it dawned on us that he was now heading toward other tents and the main lodge. We sensed that other guests were about to get their own rush of adrenaline. Or something worse. It was now obvious we were just the first stop on his afternoon rampage around Pom Pom Camp.

Keeping a safe distance, we followed him toward the main lodge to alert the staff. The pesky pachyderm disappeared somewhere, so we figured the scare was over and we headed to the dipping pool for relief from the hot temperature and the burning excitement. Sipping cool drinks, in cool water, we marveled at this surreal experience, and blood pressure returned to normal–for all of 15 minutes.

Then suddenly he was back! I dropped my jaw and my drink as he sauntered just 15 yards from us, along the path on the other side of a ridiculously flimsy (ergo, useless) fence around the pool. I pondered how its ornate, decorative woodwork might merely serve as a quaint frame around our trampled bodies. “This is insane,” Ana yelped.

Amazingly, the elephant ignored us, more concerned about those yummy succulent upper branches on the nearby tree. The camp manager screamed a few choice African obscenities at the beast, angry that the nearby foliage was progressively diminishing as the tourism season wore on.

A woman visiting from Paris was cursing at the beast in French, (I’m not sure what language the elephant preferred) and she screamed something to the likes of “Holy Toledo, Pierre!” at her husband, who was oblivious, butt-naked and vulnerable in his tent’s outdoor shower, just steps away from the uninvited monster.

“Pierre, Pierre, Pierre… get out of there!” she screamed. Then I think she said: “EXIT-vous, tout-suite, tout-suite, you idiot. You are going to get trampled to death!

E-L-E-P-H-A-N-T!”

It was such an elegant, righteous accent, sounding a touch romantic, as only the French can sound, even when they are cursing. I thought Pierre was about to lose his towel too.

Shortly thereafter, I decided I’d accompany the camp manager, Niles, and another guest, Summer, a very nice young woman from Australia, to her tent to fetch her bags. She was to hop the puddle-jumper Cessna in an hour, headed to another tent camp a few hundred miles away.

I knew the elephant was over near her tent, and I grabbed my camera equipment hoping for yet more photos of the camp tramper. I remained in the Land Cruiser when Niles and Summer went to get her bags. Suddenly it was way too quiet. And I felt alone. By golly, I was alone. And awkwardly vulnerable, and feeling silly in very rear seat of the multi-seat safari Land Cruiser, nervously waiting longer than I wanted. “Where the heck are they?” I mumbled.

Then my thoughts turned to the beast. Where was HE ?

Suddenly, I heard screams and shrieks emerge from the tent, then saw two of the camp staff ladies, clad in their proper African camp garb, running for their dear lives…like their pants were on fire. But they didn’t wear pants. I’ve never seen ladies in African dresses run faster in my life. Wait, this was my FIRST time in Africa–I had NEVER seen African woman run, period. They were screaming and running and fluttering their hands like NFL officials at a playoff game. It was the kind of evasive action people take when they come upon and disturb a bee’s nest. I wondered, “Holy moly, what’s going on now?”

With the ladies long gone across camp grounds, I peered back over to the tent where Niles and Summer had disappeared.

Then the bushes started rustling and out of nowhere came the giant, with all due haste. He was snorting and thrashing and moving faster than a locomotive, and he was looking at me–again. Dammit.

The charge.

Never in my life have I felt more raw emotions at one time. Despite the eye-popping emotions, and the realization that my life was just about over, I fell back on my photographer’s instinct and reached for my camera.

What a shot this would be, I mused. And sure enough, that’s all I had time for–ONE SHOT. I tossed the camera aside and looked at the driver’s seat, three seat rows in front of me. Then ominous dread befell me. It is my time–RIGHT NOW–my time to quickly learn how to drive like a postal delivery dude, because this vehicle had a right-side steering wheel!

Are you kidding me? How the hell do you drive from the right side? And what a time to figure it out. Too late, he’s getting really close. Time for Plan B. I recalled Niles telling me that elephants will usually avoid coming right up onto a truck. Usually? Heart pounding, I trusted in ol’ Niles and chose plan B.

I jumped into the middle seat of the Land Cruiser so I’d have a sporting chance of not dying as quickly when the humungous steamroller crushes or rolls the vehicle, or simply gorges me with his huge tusks as I try to protect my expensive camera gear.

It was just like the cliche cartoon where a dynamite stick fuse burns down, and the poor fool stuck next to it sweats and says his final “Hail Mary.” I prayed to every god there ever was–the one I believe in–and all the African gods too.

And then he swung his trunk around a final time, snorted again, and–thank you African gods–stopped abruptly just 15 yards from the Land Cruiser. When the dust settled, I swear he winked at me, laughed at me, and made a right turn toward some delicious trees in the distance.

A few minutes later, still gasping for breath and thinking about the sudden need for a pacemaker, I noticed Niles and Summer gleefully skipping toward the truck with her luggage.

Niles threw the bags on the truck, started it, and glanced over his shoulder. “Sorry we took so long. By the way, did you see that elephant?”

“What elephant?” was my reply. Then I laid down across the back seat, hands over my face in stunned disbelief at all that had transpired in the past two hours. “Can we start happy hour a little early today, Niles?”

________________________________________________

Pom Pom Camp Web Site: http://www.pompomcamp.com/

Pom Pom Camp Photo Gallery: http://www.pompomcamp.com/gallery.php

The author and photographer, safe for now in the comfort of the safari truck. Until the next predator arrives.

If you liked this post, check out these Africa photo posts:

Africa: Botswana & South Africa Part I

Africa: Botswana & South Africa Part II